Main Page Content

Never Say No Managing Change In A Project

So, your project is up and running. You've defined Project Requirements and had them signed off in blood by the sponsor. All you need to do now is watch your New Model Army get on and deliver. Right? Ahhh no. Life is never that simple, and you can reasonably safely bet hard currency that the requirements will change during delivery. Managing those changes is a potential cause of massive disruption to your project and your relationship with the client if you don't do it well.Never Say

Never Say No

To a Client

Change is Bad

It's often said that Salespeople never sayNo. And it's often true - whatever the customer asks for, they invariably say

Yes, we can do that.And Project Managers generally hate that as it paints us into a corner where our projects are not under our control. Some PMs therefore retreat into a Yoda-like mantra:

- Saying Yes leads to Change

- Change leads to Lack of Control

- Lack of control leads to Suffering (which is a PM technical term for missing deadlines, budgets or quality objectives)

Nois just unacceptable to most clients. It's seen as pure stonewalling; that you're not prepared to be cooperative, or (worse) that your team just isn't competent. Either can cause you serious problems in your sponsor relationship, maintaining which is one of your top priorities.

Change is Good

On the other hand, saying

Yesto client requests tends to result in more work. In the other Yoda mantra:

- Saying Yes leads to Change

- Change leads to More Work

- More Work leads to Happiness (another PM technical term for Increased Project Revenue and Gross Profit, which you're often responsible for)

Balance - a Neat Trick

Balancing between stonewalling (pretending that nothing can be changed and rejecting all proposed changes) and accepting all proposed changes and causing major project control problems is a tough act. Trying to work it out mid-project is even tougher. Trying to work it out on the hoof is nigh on impossible. Here's the basic magic formula - if you take nothing else away from this article, take the following sentence. Put it in your wallet, stick it to your monitor, brand it on the back of your hand:Your request makes sense, but it raises potential risks and issues that might cost time and money.Use The Sentence even if the client request doesn't make sense. Some requests will, some won't, but The Sentence usually ends up with one of 2 results:

- Client backs off

- Client agrees to more time, more money or lower quality

Change Control Process

This is a process to consistently handle the inevitable Change Requests that crop up mid-project, ensuring that the good ones get through, with associated adjustments to the cost/time/quality Holy Trinity, but the bad ones don't. You maintain control of your project, you're contractually covered, the client gets what they want, but pays for it if necessary.What is a Change Request?

This one's easy: A Change Request is any request that changes the Project Requirements.Do We Need a Change Control Process?

Again, easy. Yes. Every project must have a change process. Every change request must use it. Time and time again, I've heard inexperienced clients, developers and sales people starting to say things like:This project is too small/rapid/ low-budget to have a change process.or

This change is too small to go through change control.To which I invariably respond:

Only if the project policy is to refuse all change requests- which is of course a change process, just a really simple one to operate -

or find yourselves another PM.Strict? Yes. But here's why: because Project Requirements are a contractual document, any change to Requirements is also a contractual document. If the appropriate project authorities (the Sponsor and you) haven't signed up to a Change to the Requirements, you will fail UAT, your project won't be accepted by the sponsor, and there's a good chance you won't be paid. Here's an example: a stakeholder has a wizard wheeze. It's a pretty simple change to the requirements and won't take much effort to implement. Realising this, the stakeholder takes it straight to one of the developers, who codes it up and tests it in a couple of hours. Doesn't break anything else, doesn't noticeably impact timescales or budgets. But come UAT, the Sponsor notes that the delivered site doesn't match the requirements, and rightly asks

Where did I agree to this?You cannot allow your project to get to that point, because the only honest answer is

You didn'twith the enevitable followups of

When did you agree to it?and

Who died and gave you authority over what I want.That's A Bad Place to be. You don't need to follow the same process for small CRs as large ones, though. You can use a light weight process for small CRs, as long as the 2 processes are documented and agreed, including - vitally - the definition of a small CR.

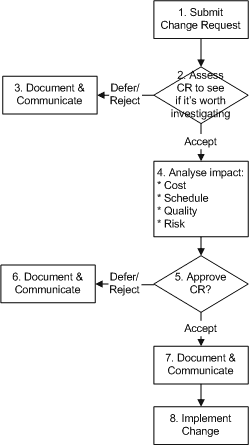

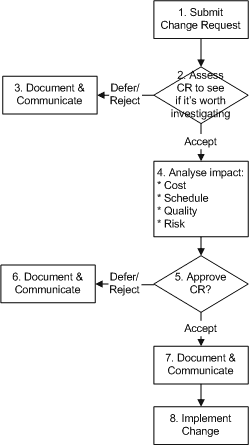

Sample Change Control Process

Here's an example of a simple Change Control Process. It's not the only possible process you could use, but it is in line with most PMI- compliant methodologies, so would be generally accepted by most professionally run projects.

- Someone submits a CR. You need to agree and document who is able to do this.

- Assess the CR to see if it's worth investigating. Here, you need to work out how long it's going to take to analyse the impact of the CR, and compare that with the projected benefits. This is a quick preflight check to weed out the obvious non-starters. If it's going to take a week just to work out how much change is involved, and the benefit is tiny, or there's not a hope in hell of it being accepted (for example, it changes the objective of the project) then this gets thrown in the bucket of

CRs that are a waste of time from the outset

. - Document and Communicate. Essential for all outcomes of any process.

- Analyse the impact. Answers the questions:

If we implement the change, how is it going to hit the Holy Trinity? What's the Risk?

To do this,

you will possibly need to replan a large chunk of the project - schedules, WBS, staffing, budgets and all. You may need time from developers for them to contribute - time they would otherwise spend delivering the project.You must have allowed for this in your original budget and schedule,

and have it explicitly written into your contract. Avoiding doing this unnecessarily is why you had the pre-assessment in step 2. - Document and Communicate

- Approve the CR? This is where you take your assessment and put it in front of your sponsor. It's then the sponsor who decides whether the CR should go ahead, accepting the changes in Schedule, Cost, Quality and Risk. If the sponsor decides against the CR, you've been co-operative and (I hope) objective in putting it forward, and you're not the one saying

No

. - Document and Communicate

- Document and Communicate

- Implement Change

Which is where your developers think the real work starts.